- Home

- Thomas Keneally

Australians: Origins to Eureka: 1

Australians: Origins to Eureka: 1 Read online

THOMAS

KENEALLY

AUSTRALIANS

THOMAS

KENEALLY

AUSTRALIANS

ORIGINS to EUREKA

VOLUME 1

First published in Australia in 2009

Copyright © Thomas Keneally 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available from the National Library of Australia

www.librariesaustralia.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74175 0690

Typeset in Minion 11.5/15pt by Midland Typesetters, Australia Printed in Australia

by Ligare Book Printer

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To four young Australian inheritors of history,

Augustus, Clementine, Alexandra and Rory.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

The way this book works

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Timeline to 1860

Notes

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The idea for this book arose from an editorial meeting, chaired by Patrick Gallagher at Allen & Unwin. So the author owes thanks to all at that table. I must also thank:

Dr Olwen Pryke, gifted researcher on this book, who has now gone on to better things at the State Library of New South Wales;

Judy Keneally, my manuscript- and proof-reading spouse, always a wise reader;

Fiona Inglis, amiable agent, for supporting me through the process and making the contract;

Rebecca Kaiser, a very genial editor-in-chief;

Amanda O’Connell, thorough and percipient copy editor;

Linda Brainwood, tireless picture researcher;

Lisa White, who designed a beautiful book;

And Kathy Mossop, Jo Lyons and Karen Ward who finally herded these pages into one pasture.

Best wishes to them all.

Thomas Keneally

THE WAY THIS BOOK WORKS

In this book I’ve tried to tell the stories of a number of Australians from the Pleistocene Age to 1860. The people whose tales are told here exemplify the major aspects and dynamisms of the Australian story. For each one I chose to write about, I could have chosen a dozen, a hundred, or in some cases, thousands more. This history therefore sets out to characterise Australia and, above all, individual Australians, in a manner which gives insight into the most significant aspects of the periods I deal with without exhaustively and thus cursorily engaging with every major actor. For example, a number of the explorers are dealt with in salient though not as thorough detail as some others are. The same is true of governors. It is in many cases with the question of how governors impacted upon individuals living on this continent that this book frequently prefers to concern itself. There are some instances where I have used material from my earlier books, The Great Shame and The Commonwealth of Thieves. I hope that those who are kind enough to read this book find this material altered to give them new perspectives, not too reminiscent of these works. I also hope that through following these histories of particular, though sometimes obscure, individuals, and by examining infrequently reported aspects of the lives of the well-known, I have managed to cast light on at least some of the mysteries of the Australian soul.

CHAPTER 1

DINNER AT CUDDIE SPRINGS

Once there was the All-Sea. Its brew of water and minerals and biology covered the planet. Then the first stones, sediments and bacteria of the great landmass Pangaea broke the surface of the encompassing ocean. They can still be found, these first gestures of ground, the original Mother Earth, in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. The question of whether Australia is old or young jangles in the Australian imagination.

At Taronga Zoo in Sydney there is a globe, at child height, showing Pangaea, the great agglomerated landmass, which remained one huge slab of earth for so long and began to break apart only about 140 million years ago. Pangaea is shown at the zoo in cut sections. A child can move the solid shapes which once made up the enormous single earth-mass on grooves, to create Laurasia in the north and Gondwana, the great southern super-continent. Then, further grooves on the surface enable the child to separate Gondwana into India, Africa, South America, Antarctica and Australia, and slide them to their present locations on the globe. Each of the pieces on this globe is marked with graphics, and as the god-playing child separates Australia from the massive Gondwana, he or she can see pictures of Australian fauna and mega-fauna abandoning the old mother super-continent, choosing Australia as their Mesozoic zoo. The separation of Australia from the rest of Gondwana began 45 million years ago.

It was not all quite as clean as the zoo game indicates. The exotic separating fragment included a version of Australia, New Guinea and Tasmania in the one gigantic landmass, named Sahul by paleontologists. It was all far to the south of where it is now. Over the next fifteen million years, Sahul edged northwards, striving, but not fully managing till three million years ago, to separate itself broadly from the Antarctic and assume a position in the primeval Pacific.

To add to the complicated picture, at various stages Sahul shrank and then expanded again. It was fifteen million years ago, for instance, that Tasmania first became an island, but then, dependent on sea levels, Sahul would regularly take it back into its mass again. The last time Tasmania separated was only 11 000 years ago, when Homo sapiens was already occupying the region, at the end of the Great Ice Age.

But Taronga Zoo’s idea of exotic animals skipping over water to get on board Sahul/Australia is a potent one. It tells the child that Australia is the continent of exotics and grotesques, and the unique story of the country surely reflects that notion for adults, too.

Modern dating methods show that the arrival of the first Australians occurred at least 60 000 years Before the Present (BP). The people who became the natives of the Australian continent first crossed from the prehistoric south-east Asian district named Wallacea between 60 000 to 18 000 BP, when the Arafura Sea was an extensive plain, when sea levels were 30 me

tres below where they are now, and there was a solid land bridge some 1600 kilometres wide between Australia and New Guinea, then joined within Sahul. Sahul’s north-western coast received only small numbers of individuals from the islands of Wallacea, possibly as few as fifty to one hundred people over a decade.

They may have come by log or canoe; they may even have waded to Sahul at low tide. If experts on human language can be believed, our species had not at that stage achieved speech, but some means of creating human co-operation would have been needed.

Descendants of these first comers still live by the hundreds of thousands in Australia, and the picture of how they lived and what they did with the continent has been revised again and again in recent times. In the early 1960s the proposal that Aboriginal people had lived in Australia for 13 000 years was thought fanciful. But carbon dating showed campfires and tools to be at least 30 000 years old, and these days experts use luminescence dating to claim that campfires and firestick burning date from more than 100 000 years ago. Almost at once as this claim was made, in 1996, at Jinmium in the Northern Territory, Australian scientists dated stone tools as 130 000 years old. If they are right, the original Australians are the oldest race on the planet. Similar remains of human activity, from before the last Ice Age, have been found on the Great Barrier Reef, on an earlier coastal line of cliffs now swamped by ocean.

We must try to imagine the earth as it was then, a country of flamingos and dangerous giant carnivorous kangaroos now known as Propelopus, of Palorchestes, the bull-sized mammal whose long snout, giraffe-like tongue and massive claws may have inspired Aboriginal tales of a swamp-dwelling, man-eating monster often called the Bunyip. The marsupial lion called Thylacoleo carnifex ranged the savannahs, and Megalania prisca, a giant lizard, made excellent eating at feasts.

These early Australians believed their ancestral beings had made the visible earth and its resources, and expected the cleaning up and fertilisation done by the firestick. A number of Australian species of tree welcomed fire—the banksia, the melaleuca, the casuarina, eucalyptus—and fire fertilised various food plants: bracken, cycads, daisy yams and grasses. The firestick, in itself and as a hunting device, may have speeded the extinction of the giant marsupial kangaroo, the marsupial lion, the giant sloth, and other species now vanished.

At Cuddie Springs, a lake bed near the north-western New South Wales town of Brewarrina, scientists have found the remains of a meal eaten over 30 000 years ago, when a spring-fed lake brimmed there and was a centre of human and animal existence. Here, in a layer of soil dated between 30 000 and 35 000 years in age, bones of Australian extinct mega-beasts have been found amongst blood-stained stone tools, charcoal and other remains of campfires. The analysis of the tools showed blood similar to that of the giant wombat-like Diprotodon. The men who had brought it down and to the cooking fire had not been immune from risk. Also at the site were found wet-milled grass and grindstones or querns, the oldest examples of such implements found anywhere. Aboriginal women thirty millennia past had a milling method which was previously thought to have begun in the Middle East only 5000 years ago.

Thus the triumph of the hunters lies over the bones of this long dead bump-nosed giant, as the triumph of the female millers of seed is evoked by the sandstone grinding basin.

There was a map of Australia in so-called prehistory too, made tribe by tribe across the landmass. The ancestor heroes and heroines had made the spiritual as well as visible earth—the landscape was a ritual, mythic, ceremonial landscape. For tens of millennia before the name Australia was applied to it, there was a clan-by-clan, ceremonial-group by ceremonial-group map of the country. In Central Australia’s desert, the Walpiri people used the term jukurrpa, Dreaming, to represent the earth as left by the ancestors, and other language groups used similar terms. The Dreaming is seen as something eternal by many white scholars and lay persons, but as one commentator says, it is a fulcrum by which the changing universe can be interpreted—the falling or rise of water levels, flood or drought, glacial steppes or deserts, the ascent or decline of species, the characteristics of animals. Another scholar is particularly worth quoting: The Dreaming ‘binds people, flora, fauna and natural phenomena into one enormous inter-functioning world’.

For the individual native, the knowledge, ritual and mystery attached to maintaining the local earth were enlarged at initiation, and further secrets were acquired through life and through dreams. A network of Dreaming tracks existed, criss-crossing the continent, certainly densely criss-crossing the Sydney Basin, connecting one well of water or place of protein or shelter with another. The eastern coastline of New South Wales, built up of Hawkesbury sandstone, standing above the sea in great platforms and easily eroded to make caves, was full of such holy sites. As a visible symbol of that, there exists a huge number of pecked and abraded engravings of humans, ancestors, sharks and kangaroos on open and sheltered rock surfaces around Sydney, as the sandstone proved a good medium for that work.

Natives at particular ceremonial sites re-enacted the journey and acts of creation of a particular hero ancestor, and by doing that they sustained the earth. As in other places the priest became Christ at the climax of the liturgy, during the natives’ re-enactment they became the hero ancestor. These people would ultimately be called by early European settlers ab origines—people who had been here since the beginning of the earth—and though they had not been on Sahul or Australia ab origine, they had been in place long enough to make that issue a quibble.

In what is now western New South Wales, near Lake Nitchie, some 6800 years ago, a number of members of the species Homo sapiens worked for the better part of a week cutting a pit into hard sediments and making it large enough to take the body of an important man. He was a tall man, some 182 centimetres in height. He had died in his late thirties from a dental abscess. In 1969 the body was found, still seated after millennia, legs bent under his torso, and head and shoulders forced down to fit him into the grave pit and bury him before he putrefied. Daubed with red ochre, a solemn ornamentation, he was interred with scraps of pearl shell which had somehow reached this distant inland location, a lump of fused silica from a meteor and a necklace of 178 Tasmanian devil’s teeth. The Tasmanian devil became extinct in mainland Australia nearly seven thousand years ago. This man was a figure of significance and power—his necklace and the care taken to inter him showed that.

Not that the man of Lake Nitchie is the oldest of rediscovered burials in Australia. A female cremation burial from 26 000 years past was found at Lake Mungo in western New South Wales. The light-boned woman’s body was not totally consumed by flames when it was cremated on the beach of vast Lake Mungo, and the remaining bones were broken up and placed in a pit. Then half a kilometre distant, but some two thousand years older, a body, almost certainly a woman’s, her right shoulder badly afflicted with osteoarthritis, and her skin ornamented with red ochre, was found partly cremated and then buried. Both these people were Homo sapiens and it is likely that their cosmology coincided in essentials with that of the Aborigines the first visiting Asians and Europeans would encounter.

Yet what would cause any intrusion on this most ancient of all human cultures? The continent the Aborigines inhabited and nurtured seemed subject to only casual and inexact European interest.

CHAPTER 2

THE MAKASSAR WELCOME

For perhaps a hundred years before the arrival of Captain Cook’s Endeavour on the east coast of Australia, a fleet of fifty or more Indonesian prahus, left the old port city of Makassar (now Ujung Pandang) for the coastline of Australia to seek trepang, a leathery sea cucumber consumed as a health food and aphrodisiac throughout Asia. For the next two hundred years the Yolngu Aboriginals of the tropics knew to expect the Makassar men when they saw the first lightning of the rainy season. The prahus, with their tripod masts and lateen sails, made landfall mainly in the land they called Marege, Arnhem Land, or else a long way to the west on the Kimberley coast, known to the Makassans

as Kayu Jawa. Each prahu carried about thirty crew members, and they dived for the trepang in groups of two to six vessels. Beach encampments of Makassans the Yolngu permitted and welcomed on their coast might have a population of two hundred men at a time. These men gathered trepang by hand or spear but the most common method of collection was diving.

The Yolngu and the Makassans went about their annual time together in a peaceful and ordered way. It was not in the interests of the Makassans to alienate the Aboriginal elders, nor the young Yolngu men they attracted to work with them, nor the young women from whom they sought sexual favours. The Makassans spent most of the day at sea. The trepang was cooked after boiling in a pan of mangrove bark, which added colour and flavour. Next it was dried out and then buried in the sand, to be dug up in time and boiled again. Then it was smoked over a slow fire in a smokehouse assembled from rattan and bamboo carried on the ships. Every few weeks they moved on to a new camp.

These Makassan visits became known to British mariners, who sometimes encountered the prahus, and would be one of the reasons the naval officer Matthew Flinders would be encouraged to circumnavigate the continent and thus demonstrate—as one historian says—that the continent was a unified and closed body that could be unilaterally possessed. In 1803 Flinders discovered six prahus off the Arnhem Land coast, and greeted their ‘Malay commanders’ to his ship: ‘The six Malay commanders shortly afterwards came on board in a canoe. It happened fortunately that my cook was Malay, and through this means I was able to communicate with them. The chief of the six prahus was a short, elderly man named Pobassoo.’ Pobassoo told Flinders that there were sixty prahus along the coast, and that a man named Salloo was the overall leader. Since they were Muslims, they were repelled by the penned hogs on board Flinders’s ship but were happy to take a bottle of port away with them.

That year, as for years before and after, as many as one thousand men, all from the Gulf of Bone in the Celebes (now Sulawesi), were working the Arnhem Land coast. They interbred with the Yolngu people, who traded turtle shells and buffalo horns with the Makassans for steel knives and fabric.

Confederates

Confederates Flying Hero Class

Flying Hero Class Gossip From the Forest

Gossip From the Forest Schindler's List

Schindler's List Bring Larks and Heroes

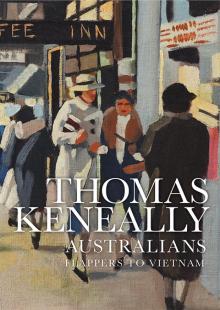

Bring Larks and Heroes Australians: Flappers to Vietnam

Australians: Flappers to Vietnam The People's Train

The People's Train Crimes of the Father

Crimes of the Father A Family Madness

A Family Madness A Commonwealth of Thieves

A Commonwealth of Thieves Ned Kelly and the City of Bees

Ned Kelly and the City of Bees A River Town

A River Town Bettany's Book

Bettany's Book Blood Red, Sister Rose: A Novel of the Maid of Orleans

Blood Red, Sister Rose: A Novel of the Maid of Orleans Victim of the Aurora

Victim of the Aurora American Scoundrel American Scoundrel American Scoundrel

American Scoundrel American Scoundrel American Scoundrel Three Cheers for the Paraclete

Three Cheers for the Paraclete Australians: Origins to Eureka: 1

Australians: Origins to Eureka: 1 The Power Game

The Power Game The Chant Of Jimmie Blacksmith

The Chant Of Jimmie Blacksmith The Daughters of Mars

The Daughters of Mars Searching for Schindler

Searching for Schindler The Great Shame: And the Triumph of the Irish in the English-Speaking World

The Great Shame: And the Triumph of the Irish in the English-Speaking World Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln The Widow and Her Hero

The Widow and Her Hero Eureka to the Diggers

Eureka to the Diggers Shame and the Captives

Shame and the Captives The Survivor

The Survivor Jacko: The Great Intruder

Jacko: The Great Intruder The Book of Science and Antiquities

The Book of Science and Antiquities Homebush Boy

Homebush Boy The Playmaker

The Playmaker To Asmara: A Novel of Africa

To Asmara: A Novel of Africa A Woman of the Inner Sea

A Woman of the Inner Sea The Tyrant's Novel

The Tyrant's Novel Australians

Australians Schindler's Ark

Schindler's Ark The Soldier's Curse

The Soldier's Curse Australians, Volume 3

Australians, Volume 3 Blood Red, Sister Rose

Blood Red, Sister Rose A Victim of the Aurora

A Victim of the Aurora The Unmourned

The Unmourned Australians, Volume 2

Australians, Volume 2 To Asmara

To Asmara